The Piper Findlater, V.C., gives his final performance at the Alhambra Theatre in London. The previous October on India's NW frontier, Findlater, a piper with the Gordon Highlanders, had been shot through both legs during the charge at Dargai. Somehow, cradling his precious pipes, he managed to drag himself to a rock. There, though bloodied, he propped himself up and continued to play "Cock o'the North." The scene so inspired his fellow Scots that they swept up the hill in face of intense fire and routed the Pathans in savage fighting.

Among the many battlefield honors won on Dargai Day was the coveted Victoria Cross for the doughty piper. The piper's tale was soon told across Britain. Discharged for his wounds and back in London, Findlater was a star attraction. The Alhamabra management signed him for £30 a week to just play "Cock o'the North." This was a not inconsiderable sum when compared with the financial reward for his heroism: his VC annuity of £10 a year plus a medical pension of two shillings a day. The War Office nonetheless frowned and officers of the highest rank cowed the Alhambra into a quick surrender. Findlater, it is announced, is released from his contract per the wishes of the Commander-in-Chief, Sir Garnet Wolseley, who feels the performance is "not in countenance with the traditions of the Army."

Findlater is offered a position in Her Majesty's Household. In Parliament, however, questions are raised about "this official interference with the free action of a discharged soldier." Mr. Broderick, the War Minister replied that it had been considered "repugnant to military feeling that an exhibition should be made at a music hall of a soldier so recently decorated by the Queen." Still, many members demanded that War Office increase the VC annuity, unchanged since 1854. The Piper's own MP from Aberdeen reminded the War Secretary "that several VC men are known to have lately ended their days either in workhouse or in great destitution." In fact, one VC winner had forfeited his medal when convicted of theft to - he claimed - support his family. The War Office soon raised the annuity to £50.

Photo from AngloBoerWarMuseum.com

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

May 30, 1842 --- A Daring Plan

In a plan both brave and foolhardy, Victoria and Albert go for a carriage ride, hoping to draw out a man, seen the day previous, taking aim at the royal landau with a pistol. The suspicious character was heard to mutter, "I was a fool that I did not shoot."

The lure works. On Constitution Hill, the man reappears, described by Albert as "a little swarthy, ill-looking rascal." As the carriage races past, this time, the gunman pulls the trigger. The gun is unloaded. Royal equerries quickly seize the man, identified as John Francis, the son of a Covent Garden cabinetmaker. A woman heard him say: "Damn the Queen; why should she be such an expense to the nation."

As she returns to Buckingham Palace, the Queen's "anxious cast of countenance" stirs much sympathy. She had gone out without her usual ladies-in-waiting, "I must expose the lives of my gentlemen but I will not expose the lives of ladies." To her uncle, King Leopold of Belgium, she concedes: "The feeling of looking out for such a man was not des plus agreables." Albert recalls, "Our minds were not very easy. We looked behind every tree."

Francis is quickly dragged before a meeting of the full Privy Council, including the Duke of Wellington, as rumors of a "conspiracy of the blackest dye" sweep London. The Illustrated London News gives thanks in the typical fashion: "The passions of the millions are indignant in the conviction of her peril, but the heart of the empire is electric with the joy of her escape." The simple Francis obviously acted alone. Sentenced to hang for treason, he was instead transported for life.

In July, there was another attempt on the Queen's life. "A hunchback little miscreant" named Bean aimed a pistol loaded with tobacco at the Queen. Albert thought the rash of incidents could be traced to "the increase of democratical & republican Notions & the licentiousness of the Press."

The lure works. On Constitution Hill, the man reappears, described by Albert as "a little swarthy, ill-looking rascal." As the carriage races past, this time, the gunman pulls the trigger. The gun is unloaded. Royal equerries quickly seize the man, identified as John Francis, the son of a Covent Garden cabinetmaker. A woman heard him say: "Damn the Queen; why should she be such an expense to the nation."

As she returns to Buckingham Palace, the Queen's "anxious cast of countenance" stirs much sympathy. She had gone out without her usual ladies-in-waiting, "I must expose the lives of my gentlemen but I will not expose the lives of ladies." To her uncle, King Leopold of Belgium, she concedes: "The feeling of looking out for such a man was not des plus agreables." Albert recalls, "Our minds were not very easy. We looked behind every tree."

Francis is quickly dragged before a meeting of the full Privy Council, including the Duke of Wellington, as rumors of a "conspiracy of the blackest dye" sweep London. The Illustrated London News gives thanks in the typical fashion: "The passions of the millions are indignant in the conviction of her peril, but the heart of the empire is electric with the joy of her escape." The simple Francis obviously acted alone. Sentenced to hang for treason, he was instead transported for life.

In July, there was another attempt on the Queen's life. "A hunchback little miscreant" named Bean aimed a pistol loaded with tobacco at the Queen. Albert thought the rash of incidents could be traced to "the increase of democratical & republican Notions & the licentiousness of the Press."

May 29, 1884 --- An Ideal Husband?

Queen Victoria's absence fails to halt the marriage of Oscar Wilde at St. James', Paddington; the groom quips, "In this fine weather, I asked her to remain at Osborne." His bride is Constance Lloyd, grand-daughter of a wealthy Irish attorney. Wilde's friend Frank Harris thought Constance was a woman "without any particular qualities or beauty" and there were many whispers that the impecunious poet-playwright is marrying for money. Indeed, the wedding has been delayed a month to allow Oscar time to settle several outstanding debts.

He met Constance in May of 1881 and told his mother that night, "By the by, Mama, I think of marrying that girl." Upon her betrothal, Constance wrote her brother, "I am...perfectly and insanely happy." The church is packed, not the least with reporters who devote most of their attention to the ladies attire, designed by the famous aesthete himself. The wedding gown is made of "rich creamy satin... with a delicate cowslip tint." Six bridesmaids, all Constance's cousins, are in "ripe gooseberry" silk. For once, Oscar goes unnoticed.

In Paris for the honeymoon, Wilde tells a reporter that as Disraeli brought art to English oratory, he shall demonstrate the "pervading influence of art on matrimony." Meeting a friend, Robert Sherard, Oscar insists on sharing explicit details of his wedding night; "It's so wonderful when a young virgin ..." is where Sherard cut him off.

Despite the timely and helpful death of Grandfather Lloyd, Oscar soon exhausted Constance's fortune in the fitting out of their new home in Chelsea. Within four months, Constance was pregnant with the first of their two sons. Choosing to spend her time with the boys, Constance became - in the words of one of Wilde's biographers - "an exquisite shade."

Following the scandal of 1895 (see 25 May), she took the name Holland and forbade Oscar from seeing the boys. They never divorced. She once said, "My poor misguided husband...is weak rather than wicked." Constance died of spinal paralysis in April of 1898. She was 40. The photograph shows Constance with her son, Cyril.

He met Constance in May of 1881 and told his mother that night, "By the by, Mama, I think of marrying that girl." Upon her betrothal, Constance wrote her brother, "I am...perfectly and insanely happy." The church is packed, not the least with reporters who devote most of their attention to the ladies attire, designed by the famous aesthete himself. The wedding gown is made of "rich creamy satin... with a delicate cowslip tint." Six bridesmaids, all Constance's cousins, are in "ripe gooseberry" silk. For once, Oscar goes unnoticed.

In Paris for the honeymoon, Wilde tells a reporter that as Disraeli brought art to English oratory, he shall demonstrate the "pervading influence of art on matrimony." Meeting a friend, Robert Sherard, Oscar insists on sharing explicit details of his wedding night; "It's so wonderful when a young virgin ..." is where Sherard cut him off.

Despite the timely and helpful death of Grandfather Lloyd, Oscar soon exhausted Constance's fortune in the fitting out of their new home in Chelsea. Within four months, Constance was pregnant with the first of their two sons. Choosing to spend her time with the boys, Constance became - in the words of one of Wilde's biographers - "an exquisite shade."

Following the scandal of 1895 (see 25 May), she took the name Holland and forbade Oscar from seeing the boys. They never divorced. She once said, "My poor misguided husband...is weak rather than wicked." Constance died of spinal paralysis in April of 1898. She was 40. The photograph shows Constance with her son, Cyril.

May 28, 1839 --- The Madman Thom

Kent is aroused by a messianic madman whose brief rising ends tragically. John Thom had achieved notoriety earlier in the decade by claiming to be Sir William Honywood Courtenay, of unacknowledged relation to the Royal Family. Failing to win a seat in Parliament, he got mixed up in a smuggling affray and was sent to a lunatic asylum in 1833.

Declared harmless and released in 1837, he soon reverted to form. Described by contemporaries as "remarkably handsome and eloquent," Thom, proclaiming himself "Savior of the World," sets out from Boughton. He has 100 followers by nightfall. Drilling his ragtag "troops" at Goodnestone, he pronounces it time to "strike the bloody blow." Barns and fields of those who refuse to join the crusade are torched. The first blood is shed at Bossenden when Thom shot to death the local constable. A small army detachment is sent out from Canterbury but their commanding officer, a Lt. Bennett, is slain while approaching to parley. The return fire is merciless and Thom is the first to fall, his dying words, "I have Jesus in my heart." Eight of his followers are killed, many more wounded.

Having signed himself as Sir William, Thom left a rambling manifesto, which concluded: "England would be better served if 12 honest tradesman, 12 honest farmers and 12 poor labourers were elected to serve their people rather than the present ignorant House of Commons... England must go to a revolution." Having pledged immortality to those who followed him, Thom was buried quickly by authorities who thought it wise to omit the references to resurrection at brief graveside rites.

In London, most observers wrote it all off to an easily deluded peasantry, yet The Spectator wondered: "What must be the condition of that society in which a madman could produce such a disastrous and frightful exhibition of popular fury?"

Declared harmless and released in 1837, he soon reverted to form. Described by contemporaries as "remarkably handsome and eloquent," Thom, proclaiming himself "Savior of the World," sets out from Boughton. He has 100 followers by nightfall. Drilling his ragtag "troops" at Goodnestone, he pronounces it time to "strike the bloody blow." Barns and fields of those who refuse to join the crusade are torched. The first blood is shed at Bossenden when Thom shot to death the local constable. A small army detachment is sent out from Canterbury but their commanding officer, a Lt. Bennett, is slain while approaching to parley. The return fire is merciless and Thom is the first to fall, his dying words, "I have Jesus in my heart." Eight of his followers are killed, many more wounded.

Having signed himself as Sir William, Thom left a rambling manifesto, which concluded: "England would be better served if 12 honest tradesman, 12 honest farmers and 12 poor labourers were elected to serve their people rather than the present ignorant House of Commons... England must go to a revolution." Having pledged immortality to those who followed him, Thom was buried quickly by authorities who thought it wise to omit the references to resurrection at brief graveside rites.

In London, most observers wrote it all off to an easily deluded peasantry, yet The Spectator wondered: "What must be the condition of that society in which a madman could produce such a disastrous and frightful exhibition of popular fury?"

May 27, 1856 --- Palmer the Poisoner

After a two week trial at the Old Bailey, Dr. William Palmer is convicted of murder. Of all the doctor-killers in Victorian England (and, alarmingly, there were quite a few), none is more infamous than the surgeon from Rugeley. Yet Dickens, who attended the trial, recalled Palmer's "constant coolness, his profound composure, his perfect equanimity."

Tied by some to as many as fourteen deaths, (including his wife, his mother-in-law and his brother), Palmer was tried for just one, the strychnine murder of John Cook. Palmer and Cook were fellow men of the Turf; Cook owned horses, Palmer bet on them, both with indifferent results. Ironically, it was shortly after one of their rare victories that Cook took violently ill. He told friends, "I swear that damned Billy Palmer dosed me." The prosecution laid out an undeniable record of swindle and forgery, but the medical evidence was inconclusive. A parade of doctors passed before the jurors; seven arguing death due to poisoning, eleven willing to suggest a non-criminal cause of death, most often, tetanus.

Despite the obvious disagreement among the experts, the jury returned a speedy verdict. Lord Chief Justice Campbell dons the traditional black cap to pronounce the death sentence, declaring from the bench: "However destructive poison may be, it is ordained by Providence, for the safety of its creatures, that there are means of detecting and punishing those who administer it." The doctor's lawyer petitioned the Home Secretary to delay the hanging until discrepancies in the medical evidence could be answered. Petition denied.

Palmer was returned to Staffordshire to hang at the county gaol on 14 June before 30,000 people. Asked by the warden if he had any confession to make, Palmer reiterated, if equivocally, "I am innocent of poisoning Cook by strychnine." With unfaltering step but obvious pallor, he went to the gallows promptly at 8 a.m. In a last quip, turning to Calcraft, the veteran hangman, Palmer asked, "Are you sure this is safe?" The huge crowd shouted obscenities and roared its entire approval at the drop.

In Rugeley, officials sought Parliamentary approval to change the town's name, so notorious had become its associations. The Prime Minister said he had no objections, providing they named it after him. Once again, Mr. Palmerston's sense of humor went unappreciated.

Tied by some to as many as fourteen deaths, (including his wife, his mother-in-law and his brother), Palmer was tried for just one, the strychnine murder of John Cook. Palmer and Cook were fellow men of the Turf; Cook owned horses, Palmer bet on them, both with indifferent results. Ironically, it was shortly after one of their rare victories that Cook took violently ill. He told friends, "I swear that damned Billy Palmer dosed me." The prosecution laid out an undeniable record of swindle and forgery, but the medical evidence was inconclusive. A parade of doctors passed before the jurors; seven arguing death due to poisoning, eleven willing to suggest a non-criminal cause of death, most often, tetanus.

Despite the obvious disagreement among the experts, the jury returned a speedy verdict. Lord Chief Justice Campbell dons the traditional black cap to pronounce the death sentence, declaring from the bench: "However destructive poison may be, it is ordained by Providence, for the safety of its creatures, that there are means of detecting and punishing those who administer it." The doctor's lawyer petitioned the Home Secretary to delay the hanging until discrepancies in the medical evidence could be answered. Petition denied.

Palmer was returned to Staffordshire to hang at the county gaol on 14 June before 30,000 people. Asked by the warden if he had any confession to make, Palmer reiterated, if equivocally, "I am innocent of poisoning Cook by strychnine." With unfaltering step but obvious pallor, he went to the gallows promptly at 8 a.m. In a last quip, turning to Calcraft, the veteran hangman, Palmer asked, "Are you sure this is safe?" The huge crowd shouted obscenities and roared its entire approval at the drop.

In Rugeley, officials sought Parliamentary approval to change the town's name, so notorious had become its associations. The Prime Minister said he had no objections, providing they named it after him. Once again, Mr. Palmerston's sense of humor went unappreciated.

May 26, 1876 --- The Stolen Duchess

In the most audacious art theft of the Victorian era, Gainsborough's "Duchess of Devonshire" vanishes from Agnew's Gallery on Old Bond Street. The thief must have hid until past closing and, avoiding an ineffectual watchman, cut the painting free from its gilt frame with "no unpracticed hand" and passed it out a window to an accomplice.

The "Duchess" is one of England's best-known paintings, just sold at auction at Christie's for a price of £10,600, the highest ever in London. The art world is incredulous; who would steal such a picture of "remarkable notoriety?" Only one man, Adam Worth. Described by one expert as "the greatest criminal mastermind of the 19th Century," Worth served as Conan Doyle's real-life model for the "Napoleon of Crime," Professor Moriarty. An expatriate American employing a cadre of malfeasants, Worth specializes in burglary and fraud; a blown bank safe in Boston ($450,000), a diamond heist in Capetown ($1,000,000), a Turkish bank swindle ($400,000), etc. Living aboard a yacht, Worth often visited London. Seeing the "Duchess" in Agnew's window, he decided to steal it that very night.

Agnew's soon received a ransom demand with a piece of the canvas. The Spectator was among many publications insistent that no ransom be paid: "No picture in the country will be safe. Plate is locked up, but the pictures in our country-houses have hitherto been considered as safe as the bookcases or carpets." No ransom was paid and the sensation passed, but for periodic false claims of the portrait's recovery.

Finally, in 1901, the "Duchess" was found in Chicago. By then, Worth was a dying man with impoverished children. He had, at last, fallen into the hands of the law, and spent much of the 1890's behind bars. Working through the Pinkertons, the storied American detective agency, Worth agreed to exchange the painting for a reward of £5000 paid directly to his children. After 25 years in a tube, the undamaged "Duchess" hung again at Agnew's. Ironically, the American banker Pierpont Morgan soon bought it for £30,000 and took it back to the U.S.

The "Duchess" is one of England's best-known paintings, just sold at auction at Christie's for a price of £10,600, the highest ever in London. The art world is incredulous; who would steal such a picture of "remarkable notoriety?" Only one man, Adam Worth. Described by one expert as "the greatest criminal mastermind of the 19th Century," Worth served as Conan Doyle's real-life model for the "Napoleon of Crime," Professor Moriarty. An expatriate American employing a cadre of malfeasants, Worth specializes in burglary and fraud; a blown bank safe in Boston ($450,000), a diamond heist in Capetown ($1,000,000), a Turkish bank swindle ($400,000), etc. Living aboard a yacht, Worth often visited London. Seeing the "Duchess" in Agnew's window, he decided to steal it that very night.

Agnew's soon received a ransom demand with a piece of the canvas. The Spectator was among many publications insistent that no ransom be paid: "No picture in the country will be safe. Plate is locked up, but the pictures in our country-houses have hitherto been considered as safe as the bookcases or carpets." No ransom was paid and the sensation passed, but for periodic false claims of the portrait's recovery.

Finally, in 1901, the "Duchess" was found in Chicago. By then, Worth was a dying man with impoverished children. He had, at last, fallen into the hands of the law, and spent much of the 1890's behind bars. Working through the Pinkertons, the storied American detective agency, Worth agreed to exchange the painting for a reward of £5000 paid directly to his children. After 25 years in a tube, the undamaged "Duchess" hung again at Agnew's. Ironically, the American banker Pierpont Morgan soon bought it for £30,000 and took it back to the U.S.

May 25, 1895 --- "A Prisoner of No Importance"

At London's Old Bailey, Oscar Wilde is convicted of sodomy and sentenced to two years hard labor. Thus, in a mere three months time, his cataclysmic downfall is complete. In 1895, Wilde was at the peak of his fame; he had two plays running in the West End, including the new hit, The Importance of Being Earnest. His private life is less praiseworthy; married with two sons, Wilde had conducted a flagrant relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas which had achieved unspoken notoriety.

Only days after Earnest opened, Douglas' father, the Marquis of Queensberry left a card at Wilde's club which read, "To Oscar Wilde: posing as a somdomite [sic]." Wilde ignored advice to ignore the card and sued for libel, a disastrous decision. Enough evidence was introduced to make a case for the truth of the claim and the Marquis was acquitted. That very day - 5 April - Wilde was arrested at the Cadogan Hotel.

His first trial ended in a hung jury. It is best remembered for Wilde's famous remark from the dock about "the love that dare not speak its name." Awaiting re-trial, Wilde was freed on bail for the first time. Friends encouraged him to flee the country, a steam yacht aboil on the Thames for that very purpose. He refused to bolt, calling it "nobler and more beautiful to stay." Yet, it was the ugly details that prove his undoing; boy prostitutes, compromising letters, even the stained bedclothing from his suite at the Savoy, re-hashed in the second trial. Wilde's defense, headed by Sir Edward Clarke, attacks his accusers as common blackmailers. However, for the Crown, Sir Frank Lockwood argues: "Were it not that there are men willing to purchase vice in the most hideous and detestable form, there would be no opening for these blackmailers to ply their calling."

Justice Alfred Wills presiding, calls it "the worst case I have ever tried ... you, Wilde, have been the center of a circle of extensive corruption of the most hideous kind." The sentence is the severest allowed under the law. Wilde, reeling noticeably, cries out, "My God ... May I say nothing, my Lord?" With a dismissive wave from the judge, Wilde is led away to gaol and oblivion. Outside, a ragged crowd jeers its approval and harlots dance in the crowded street.

The Press cry is almost unanimous; e.g. The National Observer: "There is not a man or woman in the English-speaking world possessed of the treasure of a wholesome mind who is not under a deep debt of gratitude to the Marquess of Queensberry for destroying the High Priest of the Decadents." The Penny Illustrated Paper featured this mockingly titled sketch.

Only days after Earnest opened, Douglas' father, the Marquis of Queensberry left a card at Wilde's club which read, "To Oscar Wilde: posing as a somdomite [sic]." Wilde ignored advice to ignore the card and sued for libel, a disastrous decision. Enough evidence was introduced to make a case for the truth of the claim and the Marquis was acquitted. That very day - 5 April - Wilde was arrested at the Cadogan Hotel.

His first trial ended in a hung jury. It is best remembered for Wilde's famous remark from the dock about "the love that dare not speak its name." Awaiting re-trial, Wilde was freed on bail for the first time. Friends encouraged him to flee the country, a steam yacht aboil on the Thames for that very purpose. He refused to bolt, calling it "nobler and more beautiful to stay." Yet, it was the ugly details that prove his undoing; boy prostitutes, compromising letters, even the stained bedclothing from his suite at the Savoy, re-hashed in the second trial. Wilde's defense, headed by Sir Edward Clarke, attacks his accusers as common blackmailers. However, for the Crown, Sir Frank Lockwood argues: "Were it not that there are men willing to purchase vice in the most hideous and detestable form, there would be no opening for these blackmailers to ply their calling."

Justice Alfred Wills presiding, calls it "the worst case I have ever tried ... you, Wilde, have been the center of a circle of extensive corruption of the most hideous kind." The sentence is the severest allowed under the law. Wilde, reeling noticeably, cries out, "My God ... May I say nothing, my Lord?" With a dismissive wave from the judge, Wilde is led away to gaol and oblivion. Outside, a ragged crowd jeers its approval and harlots dance in the crowded street.

The Press cry is almost unanimous; e.g. The National Observer: "There is not a man or woman in the English-speaking world possessed of the treasure of a wholesome mind who is not under a deep debt of gratitude to the Marquess of Queensberry for destroying the High Priest of the Decadents." The Penny Illustrated Paper featured this mockingly titled sketch.

May 24, 1871 --- Murdered by a Mistress

"The Bayswater Mystery," in the disapproving words of The Times, "reveals a state of things too well known to a large part of the London world, too little known to the rest." Frederick Moon, son of Sir Francis Moon, a respected Alderman in the City, is found murdered, stabbed to death by his mistress, who weeps, "I fear I did it in a scuffle."

The younger Moon, a bachelor at 41 and a wealthy brewer, lies on the dining room floor in the home of "Mrs." Flora Davy. It is a most unconventional establishment, presided over by a mysterious "Captain" Davy and tenanted by several single women. "Mrs." Davy, it turns out, is Hannah Newington, whose husband had left for Australia some years before "owing to her bad conduct." She had been Moon's mistress for twelve years. The dining room is in disarray; shattered crockery, an overturned coal-scuttle, and a bloody carving knife amid the debris. Before she was led away, "Flo" - as Moon knew her - is permitted a last kiss on her dead lover's lips.

She was soon indicted for murder, a charge reduced before her trial to manslaughter. Several acquaintances of the couple would testify to their frequent quarrels. A Capt. Elliot recalled Flo's vow, "By Jove, I will stab you someday." Portrayed by her doctors as "an habitual drunkard," Flo stands accused of stabbing her lover in a drunken rage after he had threatened to end their relationship. Under the law of England at the time, she cannot take the stand in her defense. Defense counsel portrays Moon as a man gripped by despondency over everything from his mother's death, gambling losses at that day's Derby, to a change in the licensing laws likely to affect his business. Expert medical witnesses suggest the possibility that Flo was trying to wrestle the knife from Moon and he fell upon it during the scuffle.

In his appeal to the jury on behalf of the accused, Mr. Parry reminded them, "the sin of such a relation was not wholly on the side of the woman." The jury found her guilty of manslaughter and upon hearing the sentence of eight years, Flo fainted and had to be carried insensible from the Old Bailey.

The Times hoped the tragedy would awaken those who were "spending their lives in a sort of quicksand of social confusion and moral corruption."

The younger Moon, a bachelor at 41 and a wealthy brewer, lies on the dining room floor in the home of "Mrs." Flora Davy. It is a most unconventional establishment, presided over by a mysterious "Captain" Davy and tenanted by several single women. "Mrs." Davy, it turns out, is Hannah Newington, whose husband had left for Australia some years before "owing to her bad conduct." She had been Moon's mistress for twelve years. The dining room is in disarray; shattered crockery, an overturned coal-scuttle, and a bloody carving knife amid the debris. Before she was led away, "Flo" - as Moon knew her - is permitted a last kiss on her dead lover's lips.

She was soon indicted for murder, a charge reduced before her trial to manslaughter. Several acquaintances of the couple would testify to their frequent quarrels. A Capt. Elliot recalled Flo's vow, "By Jove, I will stab you someday." Portrayed by her doctors as "an habitual drunkard," Flo stands accused of stabbing her lover in a drunken rage after he had threatened to end their relationship. Under the law of England at the time, she cannot take the stand in her defense. Defense counsel portrays Moon as a man gripped by despondency over everything from his mother's death, gambling losses at that day's Derby, to a change in the licensing laws likely to affect his business. Expert medical witnesses suggest the possibility that Flo was trying to wrestle the knife from Moon and he fell upon it during the scuffle.

In his appeal to the jury on behalf of the accused, Mr. Parry reminded them, "the sin of such a relation was not wholly on the side of the woman." The jury found her guilty of manslaughter and upon hearing the sentence of eight years, Flo fainted and had to be carried insensible from the Old Bailey.

The Times hoped the tragedy would awaken those who were "spending their lives in a sort of quicksand of social confusion and moral corruption."

May 23, 1892 --- Deeming Meets a Noose

After a last cigar and a swig of brandy, Frederick Deeming, a con-man and killer notorious on three continents, is hanged in Melbourne, Australia. Deeming had been charged with the murder of his wife whose body was found cemented in the kitchen hearth. When the London correspondent for an Australian paper went to Deeming's former home in Rainhill, near Liverpool, to find out more about the man, he noticed a newly-cemented hearth in the farmhouse kitchen. Imagine the horror when police dug out the bodies of Deeming's first wife and their four children.

Born in Kent, Deeming married a Welsh woman named Mary James who followed him to Sydney and later, South Africa. Tiring of his ill-treatment and his failed schemes, she returned to England. In 1890, Deeming left Capetown in rather a hurry; legend had it he fled a murder charge. Home in England, posing as a wealthy rancher from the veldt, he soon married again. But Mary tracked him down and he served a brief jail term for bigamy. Once freed, and now styling himself a military man, he married Emily Mather of Liverpool. When Mary reappeared, this time, Deeming silenced her and his children forever.

With Emily, he left for Australia but within weeks of their arrival, he killed her. He was engaged again, calling himself Baron Swanston, at the time of his arrest. At his indictment, he told the magistrate, "You can put it in your pipe and smoke it." He vowed, if found innocent, to leave the courtroom and drown himself within 24 hours in the Yarra River.

The defense - not without reason - claimed Deeming was insane, a victim of "instinctive criminality" he kills from "uncontrollable impulses." The jury had none of that, nor did the Privy Council in London which refused to commute the sentence. The Spectator dismissed him as "a perfectly rotten man." Crowds flocked to see his Rainhill kitchen at Madame Tussaud's Chamber of Horrors.

Whilst in prison, Deeming had claimed to be Jack the Ripper; a vainglorious boast since he had been in jail at the time of the murders in '88. Nonetheless, a popular street ballad of the period went:

Born in Kent, Deeming married a Welsh woman named Mary James who followed him to Sydney and later, South Africa. Tiring of his ill-treatment and his failed schemes, she returned to England. In 1890, Deeming left Capetown in rather a hurry; legend had it he fled a murder charge. Home in England, posing as a wealthy rancher from the veldt, he soon married again. But Mary tracked him down and he served a brief jail term for bigamy. Once freed, and now styling himself a military man, he married Emily Mather of Liverpool. When Mary reappeared, this time, Deeming silenced her and his children forever.

With Emily, he left for Australia but within weeks of their arrival, he killed her. He was engaged again, calling himself Baron Swanston, at the time of his arrest. At his indictment, he told the magistrate, "You can put it in your pipe and smoke it." He vowed, if found innocent, to leave the courtroom and drown himself within 24 hours in the Yarra River.

The defense - not without reason - claimed Deeming was insane, a victim of "instinctive criminality" he kills from "uncontrollable impulses." The jury had none of that, nor did the Privy Council in London which refused to commute the sentence. The Spectator dismissed him as "a perfectly rotten man." Crowds flocked to see his Rainhill kitchen at Madame Tussaud's Chamber of Horrors.

Whilst in prison, Deeming had claimed to be Jack the Ripper; a vainglorious boast since he had been in jail at the time of the murders in '88. Nonetheless, a popular street ballad of the period went:

On the 23d of May, Frederick Deeming passed awayAn Australian police photograph of Deeming

This is a happy day, an East End holiday,

For the Ripper's gone away.

May 22, 1850 --- Opening for a Chef

Clubland reels with word that the General Committee of the Reform Club is looking for a new chef. Since the Reform's new building opened on Pall Mall in 1841, the brilliant but temperamental Frenchman Alexis Soyer had presided over the club's heralded kitchens, which he designed, and had been described as "spacious as a ballroom and white as a young bride." The Reform Club is headquarters to Britain's ruling Whig Party and so shocking was word of Soyer's departure, Punch was only half-jesting when the humor magazine suggested that the Whig Prime Minister Lord John Russell would have to resign as well.

In fact, Soyer's genius (rewarded with an annual salary of £1000) had been so celebrated that more radical members feared that the club - a meeting place for "reformers of the United Kingdom" - would become home to mere gastronomes. Soyer had survived several clashes with his managers, but the exact circumstances of his sudden exit remain unexplained to this day. According to his "memoirs," he objected to plans to allow members to bring "strangers" (non-members) to dine, grousing that he had no wish to work at a "restaurant."

It was for his special dinners that Soyer had become renowned and none more so than the 1846 affair on behalf of a visiting Pasha. The entire seven-course menu made the papers but attention centered on Soyer's triumphant desert, Creme d'Egypte a l'Ibrahim Pasha. A three foot tall pyramid of fruited meringue, it was topped with an edible portrait of the guest of honor, done in cream and jelly.

Soyer also found time to organize a Dublin soup kitchen in the famine years, a first-ever sanitary field-kitchen for the Crimean War and to write cookbooks with "economic and judicious" versions of his recipes for middle-class kitchens. During the Great Exhibition of 1851, Soyer resurfaced in London, opening - with typical bombast - The Gastronomic Symposium of All the Nations, at Gore House on Hyde Park.

In fact, Soyer's genius (rewarded with an annual salary of £1000) had been so celebrated that more radical members feared that the club - a meeting place for "reformers of the United Kingdom" - would become home to mere gastronomes. Soyer had survived several clashes with his managers, but the exact circumstances of his sudden exit remain unexplained to this day. According to his "memoirs," he objected to plans to allow members to bring "strangers" (non-members) to dine, grousing that he had no wish to work at a "restaurant."

It was for his special dinners that Soyer had become renowned and none more so than the 1846 affair on behalf of a visiting Pasha. The entire seven-course menu made the papers but attention centered on Soyer's triumphant desert, Creme d'Egypte a l'Ibrahim Pasha. A three foot tall pyramid of fruited meringue, it was topped with an edible portrait of the guest of honor, done in cream and jelly.

Soyer also found time to organize a Dublin soup kitchen in the famine years, a first-ever sanitary field-kitchen for the Crimean War and to write cookbooks with "economic and judicious" versions of his recipes for middle-class kitchens. During the Great Exhibition of 1851, Soyer resurfaced in London, opening - with typical bombast - The Gastronomic Symposium of All the Nations, at Gore House on Hyde Park.

Mat 21, 1880 --- So Help Me God

Charles Bradlaugh, anti-monarchist, atheist and birth control proponent, approaches the bar of the House of Commons to be seated as the newly elected member for Northampton. However, Bradlaugh proposes not to swear the usual oath, which concludes "So help me God." Instead, he offers to "solemnly, sincerely and truly declare and affirm" his allegiance. In a defiant letter printed in that morning's Times, Bradlaugh declares, "So much the worse for those who would force me to repeat words which I have scores of times declared are to me sounds conveying no clear and definite meaning."

His entry into the House prompts an uproar; irate Tories block the path of a man denounced as an "infidel blasphemer." A resolution to bar Bradlaugh is quickly introduced and debated, amid high feelings. No agreement is reached and the matter stands over for the weekend; Prime Minister Gladstone advises the Queen it is "an occasion of considerable difficulty." The break cooled few tempers. In Monday's session, Randolph Churchill read from a Bradlaugh pamphlet on the Royal family: "I loathe these small German breast-bestarred wanderers ... In their own country they vegetate and wither unnoticed. Here we pay them highly to marry and perpetuate a pauper-prince race." Churchill threw the pamphlet down and stomped on it, calling its author, "a professedly disloyal person."

The debate and accompanying theatrics ran for a month. At one point, Bradlaugh again invaded the House unwelcomed and was ordered taken to the lockup located near the base of the Clock Tower, thereby becoming history's last occupant of that historic cell. He spent the night, well-fed and visited by his supporters. But, in the end, the House voted 275-230 not to seat Bradlaugh.

The defiant electors of Northampton continued to return Bradlaugh to Westminster at every opportunity. It wouldn't be until January, 1886, when affirmation of the oath was ruled sufficient, that Bradlaugh was seated. The devoutly religious Gladstone consistently voted for seating Bradlaugh, arguing that religious tests must not be placed in the path of entry to the House, "the highest prize of an Englishman's ambition."

His entry into the House prompts an uproar; irate Tories block the path of a man denounced as an "infidel blasphemer." A resolution to bar Bradlaugh is quickly introduced and debated, amid high feelings. No agreement is reached and the matter stands over for the weekend; Prime Minister Gladstone advises the Queen it is "an occasion of considerable difficulty." The break cooled few tempers. In Monday's session, Randolph Churchill read from a Bradlaugh pamphlet on the Royal family: "I loathe these small German breast-bestarred wanderers ... In their own country they vegetate and wither unnoticed. Here we pay them highly to marry and perpetuate a pauper-prince race." Churchill threw the pamphlet down and stomped on it, calling its author, "a professedly disloyal person."

The debate and accompanying theatrics ran for a month. At one point, Bradlaugh again invaded the House unwelcomed and was ordered taken to the lockup located near the base of the Clock Tower, thereby becoming history's last occupant of that historic cell. He spent the night, well-fed and visited by his supporters. But, in the end, the House voted 275-230 not to seat Bradlaugh.

The defiant electors of Northampton continued to return Bradlaugh to Westminster at every opportunity. It wouldn't be until January, 1886, when affirmation of the oath was ruled sufficient, that Bradlaugh was seated. The devoutly religious Gladstone consistently voted for seating Bradlaugh, arguing that religious tests must not be placed in the path of entry to the House, "the highest prize of an Englishman's ambition."

May 20, 1867 --- Albertopolis

Queen Victoria, dressed in deep mourning clothes with a plain widow's cap, lays the first stone for the construction of the Hall of Arts and Sciences, which she promptly renames the Royal Albert Hall. The land, on the site of Gore House (see 7 May), on the southern side of Hyde Park, was purchased with profits from the Great Exhibition. The Prince of Wales declares that the Hall will form "a prominent feature in the scheme contemplated by my dear father for perpetuating the success of that Exhibition by providing a common center of union for science and art." Prince Albert had hoped to make Kensington a center for museums, research and cultural facilities. His critics dubbed the scheme "Albertopolis."

The Queen's remarks are brief and, as usual, barely audible to most. Frankly, she admits she'd rather not be there: "It has been with a great struggle that I have nerved myself to a compliance with the wish that I should take part in this day's ceremony." With a trowel of solid gold she spreads the mortar ("evenly and neatly" noted the admiring scribe from The Illustrated London News. The cornerstone laid, the Queen strikes it with an ivory hammer, pronouncing it "Well and truly fixed." Cannon fire resounds from the Park and an orchestra strikes up Prince Albert's own composition, "L'Invocazione all'Armonia."

Designed by Francis Fowke, the Hall opened in 1870. On that occasion, the Prince of Wales officiated alone, explaining that his mother was simply too overcome with emotion to attend the event. From opening day on, the hall has been plagued by "imperfect acoustics," specifically a persistent echo. One improvement scheme believed, albeit inexplicably, to improve the sound involved planting mushrooms on the roof. Still, according to The London Encyclopedia, Albert Hall is the only place a composer can be assured of hearing his work twice.

The Queen's remarks are brief and, as usual, barely audible to most. Frankly, she admits she'd rather not be there: "It has been with a great struggle that I have nerved myself to a compliance with the wish that I should take part in this day's ceremony." With a trowel of solid gold she spreads the mortar ("evenly and neatly" noted the admiring scribe from The Illustrated London News. The cornerstone laid, the Queen strikes it with an ivory hammer, pronouncing it "Well and truly fixed." Cannon fire resounds from the Park and an orchestra strikes up Prince Albert's own composition, "L'Invocazione all'Armonia."

Designed by Francis Fowke, the Hall opened in 1870. On that occasion, the Prince of Wales officiated alone, explaining that his mother was simply too overcome with emotion to attend the event. From opening day on, the hall has been plagued by "imperfect acoustics," specifically a persistent echo. One improvement scheme believed, albeit inexplicably, to improve the sound involved planting mushrooms on the roof. Still, according to The London Encyclopedia, Albert Hall is the only place a composer can be assured of hearing his work twice.

May 19, 1898 --- End of an Era

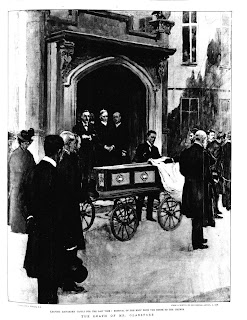

Mr. Gladstone, after a long and painful fight with cancer, dies at his country seat at Hawarden in Flintshire. It is Ascension Thursday, a fact that the devoutly religious Gladstone no doubt appreciates. In fact, he dies shortly after morning prayers; his last word, a simple "Amen." He was 88.

Four times Prime Minister, Gladstone was a man who aroused the full spectrum of emotions, but in death, several years after his political retirement, he was widely and sincerely mourned. The current Tory Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, tactfully avoids any mention of the fractious issues associated with the "Grand Old Man," choosing instead to eulogize him in the Lords as "a great example of a great Christian man." At Windsor, the Queen issues the proper public statement: "I shall ever gratefully remember his devotion and zeal." Yet, in her diary, she writes: "He was very clever and full of ideas for the betterment and advancement of the country, always most loyal to me personally, and ready to do anything for the Royal Family; but alas! I am sure involuntarily he did at times a great deal of harm." In a letter to her daughter she adds, that while "clever," Gladstone "never tried to keep up the honor and prestige of Great Britain."

At the funeral in Westminster Abbey, the Prince of Wales heads the mourners, over the Queen's objections. The Princess of Wales had written to Gladstone's widow, to praise her late husband as "one of the most beautiful upright and disinterested characters that has ever adorned the pages of history."

Mrs. Gladstone, as the bier is lowered, is heard to cry, "Once more, just once more," before she is led away by two of her sons. Two years later, the bier would be reopened for her burial at his side.

Four times Prime Minister, Gladstone was a man who aroused the full spectrum of emotions, but in death, several years after his political retirement, he was widely and sincerely mourned. The current Tory Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, tactfully avoids any mention of the fractious issues associated with the "Grand Old Man," choosing instead to eulogize him in the Lords as "a great example of a great Christian man." At Windsor, the Queen issues the proper public statement: "I shall ever gratefully remember his devotion and zeal." Yet, in her diary, she writes: "He was very clever and full of ideas for the betterment and advancement of the country, always most loyal to me personally, and ready to do anything for the Royal Family; but alas! I am sure involuntarily he did at times a great deal of harm." In a letter to her daughter she adds, that while "clever," Gladstone "never tried to keep up the honor and prestige of Great Britain."

At the funeral in Westminster Abbey, the Prince of Wales heads the mourners, over the Queen's objections. The Princess of Wales had written to Gladstone's widow, to praise her late husband as "one of the most beautiful upright and disinterested characters that has ever adorned the pages of history."

Mrs. Gladstone, as the bier is lowered, is heard to cry, "Once more, just once more," before she is led away by two of her sons. Two years later, the bier would be reopened for her burial at his side.

May 18, 1900 --- Mafeking

At 9:20 on a Friday evening, a small announcement is posted at Mansion House in London which reads: "MAFEKING IS RELIEVED!" After 217 days, a British relief column had broken the Boer siege of the British garrison at Mafeking, a border town west of Pretoria.

The garrison, commanded by Robert Baden-Powell ("B-P"), was outnumbered 6-to-1. Yet, the colorful B-P (founder of the Boy Scouts after the war) hid their weakness through deception, including dummy forts and makeshift guns. He also armed some natives, creating the "Black Watch." The infuriated Boer General Cronje called it "an enormous act of wickedness," demanding "Disarm your blacks and act the part of a white man in a white man's war!"

The lifting of the siege, while of little or no military significance, is greeted with hysteria at home by a public starved for good news. Spontaneously, cheering crowds spread the word through London. The Lord Mayor emerges to make an impromptu speech, concluding: "British pluck and valour, when used in a right cause, must triumph." Happy crowds converge on Mrs. Baden-Powell's home near Hyde Park Corner. The street demonstrations go on for days across the country and a strange new word appears in the papers: "mafficking," meaning unrestrained celebrations.

The Morning Post correspondent in Mafeking exulted, "It is good to be an Englishman ... [The Boers] are good but we are better and have proved so for several hundred years."

The oft-derided Poet Laureate, Alfred Austin, went for his rhyming dictionary.

The garrison, commanded by Robert Baden-Powell ("B-P"), was outnumbered 6-to-1. Yet, the colorful B-P (founder of the Boy Scouts after the war) hid their weakness through deception, including dummy forts and makeshift guns. He also armed some natives, creating the "Black Watch." The infuriated Boer General Cronje called it "an enormous act of wickedness," demanding "Disarm your blacks and act the part of a white man in a white man's war!"

The lifting of the siege, while of little or no military significance, is greeted with hysteria at home by a public starved for good news. Spontaneously, cheering crowds spread the word through London. The Lord Mayor emerges to make an impromptu speech, concluding: "British pluck and valour, when used in a right cause, must triumph." Happy crowds converge on Mrs. Baden-Powell's home near Hyde Park Corner. The street demonstrations go on for days across the country and a strange new word appears in the papers: "mafficking," meaning unrestrained celebrations.

The Morning Post correspondent in Mafeking exulted, "It is good to be an Englishman ... [The Boers] are good but we are better and have proved so for several hundred years."

The oft-derided Poet Laureate, Alfred Austin, went for his rhyming dictionary.

Once again, banners, fly! Clang again, bells, on high,Baden-Powell, front row center, courtesy of Scout.Org

Sounding to sea and sky, Longer and louder

Mafeking's glory with Kimberly, Ladysmith

Of our unconquered kith, Prouder and prouder.

May 17, 1849 --- The Railway King

George Hudson, rises before a sullen House of Commons to deny any wrong-doing as his rail empire collapses around him. Pausing - if only for effect - to gather his emotions, Hudson calls the charges against him "unfair", any errors on his part "unintentional", and describes himself as a man who "cares nothing for pecuniary considerations." The Times scoffs: "Since the days of non mi ricordo, we never heard such an audacious disclaimer of knowledge where knowledge was expected... indeed, ostentatiously pretended."

A linen draper from Yorkshire, Hudson had parlayed an inheritance into control of near half the railways in England. Capitalizing on the "railway mania" of the early 40's, he amassed a huge fortune and political influence as MP for Sutherland. Obese and uncouth, he bought his way into the best London society. The Railway King entertained lavishly at his splendid home at Albert Gate in Knightsbridge. As the "mania" cooled, however, disgruntled investors began raising embarrassing questions. One observer quipped: "How was Midas ruined? By keeping everything but his accounts." Stock price manipulation, paying dividends out of capital and profit-skimming are but a few of the allegations.

Weeping denials notwithstanding, Hudson is soon a ruined man. The total losses in the collapse of the railway boom in the late 40's was estimated to be £80,000,000. Endless lawsuits by vengeful investors left Hudson without fortune or reputation. The fashionable world quickly abandoned him. They delighted, too, in snubbing Mrs. Hudson, retelling how - when shown a bust of Marcus Aurelius, she asked, "Is that the present Marquis?" The society diarist Greville writes: "Most people rejoice at the degradation of a purse-proud vulgar upstart."

Until he was unseated in 1859, Hudson's MP status gave him immunity from personal debts. Driven to exile in France, he returned in 1869 and served a brief jail term. Released and provided with an annuity by grateful friends, Hudson retired modestly to Pimlico, without influence save as chairman of the smoking room at the Carlton Club.

A linen draper from Yorkshire, Hudson had parlayed an inheritance into control of near half the railways in England. Capitalizing on the "railway mania" of the early 40's, he amassed a huge fortune and political influence as MP for Sutherland. Obese and uncouth, he bought his way into the best London society. The Railway King entertained lavishly at his splendid home at Albert Gate in Knightsbridge. As the "mania" cooled, however, disgruntled investors began raising embarrassing questions. One observer quipped: "How was Midas ruined? By keeping everything but his accounts." Stock price manipulation, paying dividends out of capital and profit-skimming are but a few of the allegations.

Weeping denials notwithstanding, Hudson is soon a ruined man. The total losses in the collapse of the railway boom in the late 40's was estimated to be £80,000,000. Endless lawsuits by vengeful investors left Hudson without fortune or reputation. The fashionable world quickly abandoned him. They delighted, too, in snubbing Mrs. Hudson, retelling how - when shown a bust of Marcus Aurelius, she asked, "Is that the present Marquis?" The society diarist Greville writes: "Most people rejoice at the degradation of a purse-proud vulgar upstart."

Until he was unseated in 1859, Hudson's MP status gave him immunity from personal debts. Driven to exile in France, he returned in 1869 and served a brief jail term. Released and provided with an annuity by grateful friends, Hudson retired modestly to Pimlico, without influence save as chairman of the smoking room at the Carlton Club.

May 16, 1876 --- The Prince's Menagerie

The Zoological Gardens at Regent's Park welcome the last of the incredible menagerie collected by the Prince of Wales on his just concluded trip to India. The leading naturalist Francis Buckland crowed. "No greater event has ever occurred than the accession of the collection just made by his Royal Highness."

Two boatloads of animals had docked in Portsmouth, in all 69 mammals and 97 birds, and a bi-pedal curiosity, a Madras curry cook to join the Prince's kitchen staff. Two giant Indian elephants were given a Royal Marine escort as native mahoots drove the mighty beasts through slumbering villages along the present day A3. The rest, save the cook, are crated and caged for travel by train. Beware the tigers; a curious sailor had lost a hand on the voyage.

The simple size of the collection overwhelms the Zoological Society which can manage only ""admirable and ingenious arrangements" for the animals at first. The curious public, drawn by newspaper reports, must be kept at some distance. A good deal of interest is paid to two baby elephants, born aboard ship. Named Rustam and Omar, the calves are quite playful, "continually lifting up a foot to shake 'hands' with visitors." The inventory includes some rare species, such as the spotted porcine deer from mountainous Nepal.

If truth be told, the Prince's predilection is more toward shooting than collecting big game. While in India, several of the potentates arranged "sport" for their distinguished visitor. On one occasion, from the comfort and safety of his howdah, the Prince killed six tigers. He wrote his sons "I have had great tiger shooting. The day before yesterday I killed six, some were very savage. Two were man-eaters. Today I killed a tigress and she had a little cub with her." The cub survived to be included in the menagerie.

During the voyage, taxidermists worked round the clock preparing "the numerous and valuable natural history specimens shot by the Prince."

Two boatloads of animals had docked in Portsmouth, in all 69 mammals and 97 birds, and a bi-pedal curiosity, a Madras curry cook to join the Prince's kitchen staff. Two giant Indian elephants were given a Royal Marine escort as native mahoots drove the mighty beasts through slumbering villages along the present day A3. The rest, save the cook, are crated and caged for travel by train. Beware the tigers; a curious sailor had lost a hand on the voyage.

The simple size of the collection overwhelms the Zoological Society which can manage only ""admirable and ingenious arrangements" for the animals at first. The curious public, drawn by newspaper reports, must be kept at some distance. A good deal of interest is paid to two baby elephants, born aboard ship. Named Rustam and Omar, the calves are quite playful, "continually lifting up a foot to shake 'hands' with visitors." The inventory includes some rare species, such as the spotted porcine deer from mountainous Nepal.

If truth be told, the Prince's predilection is more toward shooting than collecting big game. While in India, several of the potentates arranged "sport" for their distinguished visitor. On one occasion, from the comfort and safety of his howdah, the Prince killed six tigers. He wrote his sons "I have had great tiger shooting. The day before yesterday I killed six, some were very savage. Two were man-eaters. Today I killed a tigress and she had a little cub with her." The cub survived to be included in the menagerie.

During the voyage, taxidermists worked round the clock preparing "the numerous and valuable natural history specimens shot by the Prince."

May 15, 1847 --- Death of the Great Dan

On a dying pilgrimage to the seat of his Church, Daniel O'Connell makes it only as far as Genoa where he succumbs to a brain tumor at the age of 71. His heart is removed for burial in Rome and the body put aboard ship for Ireland where he is beloved as "the Great Dan...the Liberator of his people."

Thousands line Dublin's River Liffey and the traditional keening wail escorts the ship bearing the body. As the coffin is borne to a waiting carriage, all kneel wherever there is space. While the grief is sorely felt, The Times - never a supporter - was, nonetheless, not wrong in its conclusion: "O'Connell had been weighed in the balance and found wanting. He was already dead to history when he left these shores."

A brawling Kerryman, an attorney who mobilized the West country masses, O'Connell fought and won in the 20's and 30's civil rights for Catholics. In the 40's, however, he was challenged by the "young Ireland" movement; men less committed to the Parliamentary struggle and "moral force." O'Connell had responded with his most strident rhetoric yet, demanding repeal of the "unfounded and unjust" Anglo-Irish Union. In 1843, his "monster" meetings drew unheard of crowds, peaking at Tara where 1.5 million people filled the ancient seat of Irish Kings. An alarmed British government ordered O'Connell to cancel his next meeting at Clontarf, vowing to use troops to disperse the crowds. O'Connell backed down. He called it "prudent, wise and, above all things, humane" but his foes called it cowardice. The Nation, Young Ireland's voice, declared: "O'Connell will run no more risks."

Although O'Connell went to jail for his "repeal efforts," his influence was all but gone upon his release. Depressed by the famine and his own poor health, O'Connell faded away. His last speech to the Commons, where he formerly incited either fierce loyalty or loathing, could barely be heard. Disraeli called it a "strange and touching spectacle." Gladstone said too much when he called O'Connell "the greatest popular leader the world has ever known," but O'Connell's countrymen have been less kind. Yeats, for example, dismissed him as "the great Comedian" contrasting his "bragging rhetoric and gregarious humor" with the "proud and silent Parnell."

O'Connell painted by Sir George Hayter

Thousands line Dublin's River Liffey and the traditional keening wail escorts the ship bearing the body. As the coffin is borne to a waiting carriage, all kneel wherever there is space. While the grief is sorely felt, The Times - never a supporter - was, nonetheless, not wrong in its conclusion: "O'Connell had been weighed in the balance and found wanting. He was already dead to history when he left these shores."

A brawling Kerryman, an attorney who mobilized the West country masses, O'Connell fought and won in the 20's and 30's civil rights for Catholics. In the 40's, however, he was challenged by the "young Ireland" movement; men less committed to the Parliamentary struggle and "moral force." O'Connell had responded with his most strident rhetoric yet, demanding repeal of the "unfounded and unjust" Anglo-Irish Union. In 1843, his "monster" meetings drew unheard of crowds, peaking at Tara where 1.5 million people filled the ancient seat of Irish Kings. An alarmed British government ordered O'Connell to cancel his next meeting at Clontarf, vowing to use troops to disperse the crowds. O'Connell backed down. He called it "prudent, wise and, above all things, humane" but his foes called it cowardice. The Nation, Young Ireland's voice, declared: "O'Connell will run no more risks."

Although O'Connell went to jail for his "repeal efforts," his influence was all but gone upon his release. Depressed by the famine and his own poor health, O'Connell faded away. His last speech to the Commons, where he formerly incited either fierce loyalty or loathing, could barely be heard. Disraeli called it a "strange and touching spectacle." Gladstone said too much when he called O'Connell "the greatest popular leader the world has ever known," but O'Connell's countrymen have been less kind. Yeats, for example, dismissed him as "the great Comedian" contrasting his "bragging rhetoric and gregarious humor" with the "proud and silent Parnell."

O'Connell painted by Sir George Hayter

May 14, 1860 --- A Perjurious Charge

After two closely watched trials, featuring charges of "an indecent description," 11-year old Eugenia Plummer is convicted of perjury.

After two closely watched trials, featuring charges of "an indecent description," 11-year old Eugenia Plummer is convicted of perjury. In the first trial, the Wiltshire girl's testimony had sent her former tutor to jail for four years with hard labor. The Rev. Henry Hatch, chaplain at Wandsworth jail (left), had sought companions for his adopted daughter by advertising as a tutor for young girls. The Plummers placed Eugenia and her 4-year old sister Stephanie with Rev. Hatch but the arrangement lasted only two weeks. Mrs. Plummer retrieved the girls, claiming that her daughters were unhappy sleeping on calico sheets. Within days, however, the Plummers complained to their Bishop that the girls had been molested.

Under the law of the day, neither Hatch nor his wife could testify at his trial. The jury was left with Eugenia's sordid tale, "narrated with steadfast countenance, with perfect mastery of the language descriptive of matters usually left in decent obscurity." Convicted, jailed and reviled, Rev. Hatch fought to clear himself from Newgate Prison. By filing perjury charges, he's now able to confront his accuser in court.

His lawyer dismisses Eugenia's tale as "entire fiction, the result of a prurient and depraved imagination." While the exact charges are "unfit for publication," Hatch admits that he and his wife did permit the girls to come into their bed, but only beneath the coverlet. Indeed, Mrs. Plummer had suggested that her daughters - who had been to several schools - needed "petting." Hatch denies parading half-naked or worse in front of the girls. Lawyers for the girl ask what motive had she to lie but Eugenia was overheard telling her sister, "I hate the Hatches." Summing up, the trial judge admits the case comes down to "contradiction upon contradiction."

May 13, 1855 --- Mr. Gladstone's "Rescue Work"

The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Mr. William Gladstone appears in Marlborough Street Court to press charges against a would-be blackmailer. The details of Gladstone's so-called "rescue work," hitherto known only to intimates, prompt "great surprise, curiosity, and interest." Gladstone has the unusual avocation of seeking out prostitutes, offering little sermons, some money and directions to an appropriate shelter.

Two nights before, returning from the opera, Gladstone had stopped to converse with one such unfortunate near Covent Garden. Suddenly, he was accosted by William Wilson, who vowed to go to the Press unless his silence was purchased with money or a government post. Promising "neither sixpence not situation," the defiant Gladstone, his tormentor at his heels, walked for blocks in a frustrating search for a policeman. By the time he found one, Wilson was in tears, begging forgiveness. Ignoring his friends, scorning controversy and embarassment, Gladstone refuses to let the matter drop. The Police Court is crowded with the curious. Gladstone details the night in question and presents a jailcell letter from Wilson: "I cannot conceive how a mere selfish and visionary aim prompted me so to act, imputing motives depreciatory of one so good and great. I beg your pardon from my very heart." The plea failed and Wilson is convicted and given a year's hard labor.

The battle won, Gladstone then pressed for Wilson's early release. The man served six months. While most of the leading newspapers covered the matter with grudging, if bemused, restraint, The People's Paper, a leading radical journal, questioned Gladstone's story: "All this may be true, but why was not the unfortunate woman produced?" In his diary, Gladstone concedes, "These talkings of mine are certainly not within the rules of worldly prudence: I am not sure that Christian prudence sanctions them for such a one as me."

But Gladstone never gave up his "rescue work." The prostitutes, especially those at "the top of the tree," knew him well; they called him "old Glad-Eye." One admiring courtesan wrote of Gladstone, "One longs to stroke that magnificent head."

Two nights before, returning from the opera, Gladstone had stopped to converse with one such unfortunate near Covent Garden. Suddenly, he was accosted by William Wilson, who vowed to go to the Press unless his silence was purchased with money or a government post. Promising "neither sixpence not situation," the defiant Gladstone, his tormentor at his heels, walked for blocks in a frustrating search for a policeman. By the time he found one, Wilson was in tears, begging forgiveness. Ignoring his friends, scorning controversy and embarassment, Gladstone refuses to let the matter drop. The Police Court is crowded with the curious. Gladstone details the night in question and presents a jailcell letter from Wilson: "I cannot conceive how a mere selfish and visionary aim prompted me so to act, imputing motives depreciatory of one so good and great. I beg your pardon from my very heart." The plea failed and Wilson is convicted and given a year's hard labor.

The battle won, Gladstone then pressed for Wilson's early release. The man served six months. While most of the leading newspapers covered the matter with grudging, if bemused, restraint, The People's Paper, a leading radical journal, questioned Gladstone's story: "All this may be true, but why was not the unfortunate woman produced?" In his diary, Gladstone concedes, "These talkings of mine are certainly not within the rules of worldly prudence: I am not sure that Christian prudence sanctions them for such a one as me."

But Gladstone never gave up his "rescue work." The prostitutes, especially those at "the top of the tree," knew him well; they called him "old Glad-Eye." One admiring courtesan wrote of Gladstone, "One longs to stroke that magnificent head."

May 12, 1891 --- Captain Verney's Disgrace

With no discussion of the "painful details" and no dissenting votes, the House of Commons takes the rare action of expelling a member. On 6 May, Capt. Edmond Verney, Conservative member for North Bucks, plead guilty to "conspiring to procure for corrupt and immoral purposes a girl of nineteen." The scandal is all the more embarassing given Verney's prominent role in the National Vigilance Association, dedicated to the abolition of vice in the great city.

Verney led a double life. Married and a 30-year Naval officer of distinguished record, whose father - "a high-minded English gentleman" - had represented the constituency for many years, Verney had the alter ego of "Mr. Wilson." Using a procuress named Madame Rouillier, he lured young women from a registry for governesses in Belgravia to clandestine meetings in Paris. Miss Nellie Blaskett proved his undoing. Brought to the French capitol, she balked when left alone with her prospective employer. The persistent "Wilson" took her to the Eiffel Tower, holding, what he called, "her pretty little hand." When Nellie still refused his entreaties, he paid her way back to London.

Some weeks later, on a winter day in Westminster, Miss Blaskett, walking with her mother, espied a man with a "peculiar walk" and cried out, "Mother, there is that beast Wilson!" Verney fled to the continent but returned to be arrested upon arrival at Charing Cross. His unavailing defense was that he had been guilty of no act of indecency and, rather, behaved as a gentleman, paying her return fare to London. In a final, unavailing, appeal for mercy, his counsel declared, "His position is lost, his rank in the Navy is gone, his honored name has departed from him." He received a one year sentence. The Tory leader, W.H. Smith calls the expulsion a "disagreeable duty."

The Press links Capt. Verney's downfall with his conspicuous zeal in the purity crusade: The Spectator opines, "Dwelling on that subject, we fear does not cleanse the mind."

Verney led a double life. Married and a 30-year Naval officer of distinguished record, whose father - "a high-minded English gentleman" - had represented the constituency for many years, Verney had the alter ego of "Mr. Wilson." Using a procuress named Madame Rouillier, he lured young women from a registry for governesses in Belgravia to clandestine meetings in Paris. Miss Nellie Blaskett proved his undoing. Brought to the French capitol, she balked when left alone with her prospective employer. The persistent "Wilson" took her to the Eiffel Tower, holding, what he called, "her pretty little hand." When Nellie still refused his entreaties, he paid her way back to London.

Some weeks later, on a winter day in Westminster, Miss Blaskett, walking with her mother, espied a man with a "peculiar walk" and cried out, "Mother, there is that beast Wilson!" Verney fled to the continent but returned to be arrested upon arrival at Charing Cross. His unavailing defense was that he had been guilty of no act of indecency and, rather, behaved as a gentleman, paying her return fare to London. In a final, unavailing, appeal for mercy, his counsel declared, "His position is lost, his rank in the Navy is gone, his honored name has departed from him." He received a one year sentence. The Tory leader, W.H. Smith calls the expulsion a "disagreeable duty."

The Press links Capt. Verney's downfall with his conspicuous zeal in the purity crusade: The Spectator opines, "Dwelling on that subject, we fear does not cleanse the mind."

May 11, 1887 --- Buffalo Bill

Queen Victoria and entourage are treated to a private viewing of Buffalo Bill's American Exhibition at Earl's Court. According to the official Court reporter, "the members of the Wild West Show went through several of their peculiar performances, finishing with the spectacle of the attack on the Deadwood coach."

The Queen has a chance to speak briefly with several of the participants, including the famed sharpshooter Annie Oakley. The Prince of Wales, as always less reserved than his mother, when he saw Annie's act, shouted, "What a pity there are not more women in the world like that little one!" The Queen also meets Red Shirt, leader of the 150 Indians from the American plains who had been the object of such intense curiosity since they pitched their teepee's in South Kensington two weeks before. At her request, the Queen is shown two papooses; "She was pleased to shake their hands and pat their painted cheeks." Buffalo Bill Cody presents himself to Victoria, asking solicitously if the show had been too long for the 68 year old Queen. "Not at all," comes the regal reply.

Returning to Windsor that evening, the Queen describes the event as "very extraordinary and interesting." The show, part of the Jubilee celebration, runs through October. With London jammed with royalty, perhaps Buffalo Bill's greatest moment came the night he managed somehow to pack the Kings of Belgium, Denmark, Greece and Saxony into one stagecoach, along with the portly Prince of Wales. The buckskinned showman called it "my Royal flush."

While some in the press were critical of the brash Cody - one scribe wrote him off as merely "an adroit scalper" - the majority of the reviews were favorable. The Daily Telegraph exulted: "Buffalo Bill, mounted on a beautiful white horse, and looking like a veritable King of men, as fine as figure as he is an admirable and elegant horseman." The Times, bowing to the two sold out shows nightly, crowned Buffalo Bill "the hero of the Season."

The Queen has a chance to speak briefly with several of the participants, including the famed sharpshooter Annie Oakley. The Prince of Wales, as always less reserved than his mother, when he saw Annie's act, shouted, "What a pity there are not more women in the world like that little one!" The Queen also meets Red Shirt, leader of the 150 Indians from the American plains who had been the object of such intense curiosity since they pitched their teepee's in South Kensington two weeks before. At her request, the Queen is shown two papooses; "She was pleased to shake their hands and pat their painted cheeks." Buffalo Bill Cody presents himself to Victoria, asking solicitously if the show had been too long for the 68 year old Queen. "Not at all," comes the regal reply.

Returning to Windsor that evening, the Queen describes the event as "very extraordinary and interesting." The show, part of the Jubilee celebration, runs through October. With London jammed with royalty, perhaps Buffalo Bill's greatest moment came the night he managed somehow to pack the Kings of Belgium, Denmark, Greece and Saxony into one stagecoach, along with the portly Prince of Wales. The buckskinned showman called it "my Royal flush."

While some in the press were critical of the brash Cody - one scribe wrote him off as merely "an adroit scalper" - the majority of the reviews were favorable. The Daily Telegraph exulted: "Buffalo Bill, mounted on a beautiful white horse, and looking like a veritable King of men, as fine as figure as he is an admirable and elegant horseman." The Times, bowing to the two sold out shows nightly, crowned Buffalo Bill "the hero of the Season."

May 10, 1894 --- A Political Wedding

It is the political and social wedding of the year; at St. George's, Hanover Square, the Home Secretary, Mr. Henry Asquith marries Margot Tennant. The congregation includes the present Prime Minister, Lord Rosebery; his predecessor, Mr. Gladstone; and two future PM's, Mr. Balfour and the groom himself. Adding to the interest is the fact that, at one time or another, Rosebery and Balfour had been rumored to be among the bride's many suitors.

Asquith, 42, is a widower; his first wife, Helen, he had met and married while a young man in Yorkshire. They had five children. Brilliant at Oxford and at the bar, Asquith rose rapidly in the Liberal Party. But in Westminster's heady social world, he moved alone. Helen preferred to stay with the children; he later wrote, "She was not the least anxious for me to 'get on.'" Dining on the terrace of the House of Commons, he met Margot. She is the youngest of the five celebrated daughters of Sir Charles Tennant, a wealthy Liberal Party patron. In her memoirs, Margot recalled. "My new friend and I ... gazed into the river and talked far into the night ... It never occured to me that he was married."

Fascinated by politics and frustrated by a woman's inability to be more than a hostess, Margot attached her ambitions to Asquith. They soon became friends, indiscrete correspondents, but not likely lovers. As for the reclusive Mrs. Asquith, Margot told friends, "She lives in Hampstead and has no clothes." In 1891, while on holiday in Scotland, Helen (conveniently?) died of typhoid. Asquith waited only the proper time before proposing to Margot. She quickly accepted.

Her friends were somewhat dismayed for Asquith is neither wealthy nor fashionable - not even interesting; another of Margot's suitors, the always amorous W.S. Blunt, thought of Asquith, "Truly, he is a dull fellow." But armed with £5000 per year from her father (which proved greatly inadequate), Margot accepted Henry. After 14 years and two children of their own, Margot and Henry arrived at 10 Downing Sheet. While there, her candor and forward ways earned her Anita Leslie's vote, in her book The Marlborough House Set, for "the most unpopular Prime Minister's wife in history."

Asquith, 42, is a widower; his first wife, Helen, he had met and married while a young man in Yorkshire. They had five children. Brilliant at Oxford and at the bar, Asquith rose rapidly in the Liberal Party. But in Westminster's heady social world, he moved alone. Helen preferred to stay with the children; he later wrote, "She was not the least anxious for me to 'get on.'" Dining on the terrace of the House of Commons, he met Margot. She is the youngest of the five celebrated daughters of Sir Charles Tennant, a wealthy Liberal Party patron. In her memoirs, Margot recalled. "My new friend and I ... gazed into the river and talked far into the night ... It never occured to me that he was married."

Fascinated by politics and frustrated by a woman's inability to be more than a hostess, Margot attached her ambitions to Asquith. They soon became friends, indiscrete correspondents, but not likely lovers. As for the reclusive Mrs. Asquith, Margot told friends, "She lives in Hampstead and has no clothes." In 1891, while on holiday in Scotland, Helen (conveniently?) died of typhoid. Asquith waited only the proper time before proposing to Margot. She quickly accepted.